The humble tree root acts as nature’s digestive system, turning essential sustenance like CO2 and water via soil. The evolution of complex root systems has been a longstanding mystery for researchers, however, a recent breakthrough sheds light on the origins of Earth’s oldest forest. Let’s take a closer look.

Roots Across Millennia

Trees owe much to their roots—literally! Extensive and efficient rooting systems are crucial for their success, allowing them to dominate diverse habitats worldwide. Modern roots, it appears, have a deeper lineage than previously thought.

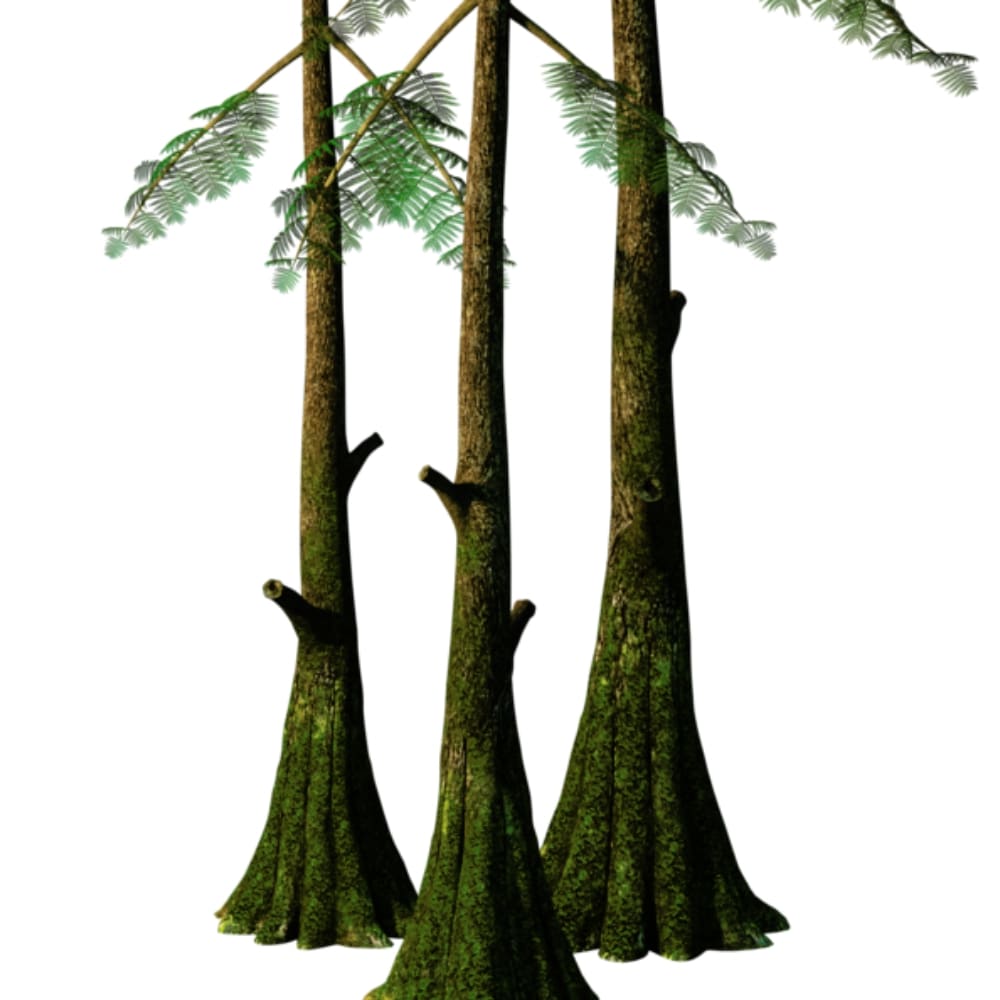

Pioneering research has revealed Earth’s oldest known forest, dating back an incredible 385 million years, a period preceding the rise of seed-producing plants. This ancient woodland is located near Cairo, New York. This forest has introduced scientists to Archaeopteris, an ancient genus believed to be the progenitor of the first modern tree. Nice.

A Very Old Tree

Archaeopteris has flat green leaves and thick, robust trunks. William Stein, a paleobotanist at Binghamton University, notes that archaeopteris possess qualities that allow it to essentially transform how plant life can come to dominate an ecosystem.

He notes that this particular tree evolution marked a significant departure from the smaller plants that dominated the landscape just a few million years earlier—sort of like an industrial revolution, but for trees!

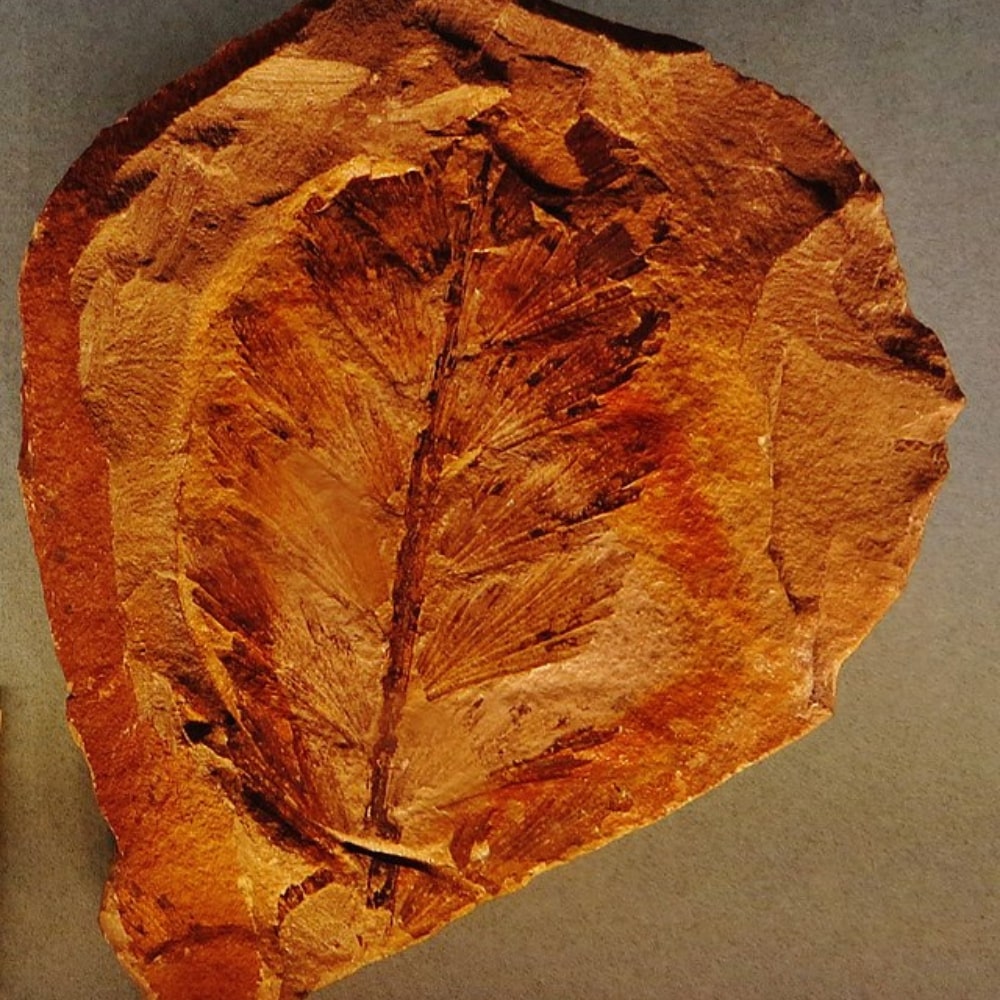

New Discoveries

The discovery at Cairo showcases a sophisticated forest ecosystem—the fossil-rich site at Cairo offers a three-dimensional view of a mid-Devonian forest, allowing scientists to understand the coexistence of different plant species and the ecosystems they formed.

With deforestation and carbon emissions threatening modern forests, the parallels between the Devonian period and today are evident. The fate of our world is intricately tied to the well-being of trees. The ancient forests, by shaping the climate and landscapes, set the stage for creating the modern world—a lesson we must heed as we navigate modern environmental challenges.

Do Spiders Dream? REM-Like Sleep Behavior in Jumping Spiders Suggests They Might

So far, only mammals and birds have been proven to dream. But now, the same team of neuroscientists who first discovered REM sleep behavior in birds has found similar patterns in another animal: jumping spiders. It suggests that dreaming — or something like it — might be more common than once thought.

The New Study and REM

A new (and genuinely adorable) study used the transparent exoskeletons of juvenile jumping spiders to track their eyes. At the same time, when they slept, they experienced rapid eye movement (REM). REM sleep is characterized by rapid eye movements, increased brain activity, and vivid dreams. It’s believed to be essential for memory and learning. During REM sleep, your breathing and heart rate also increases.

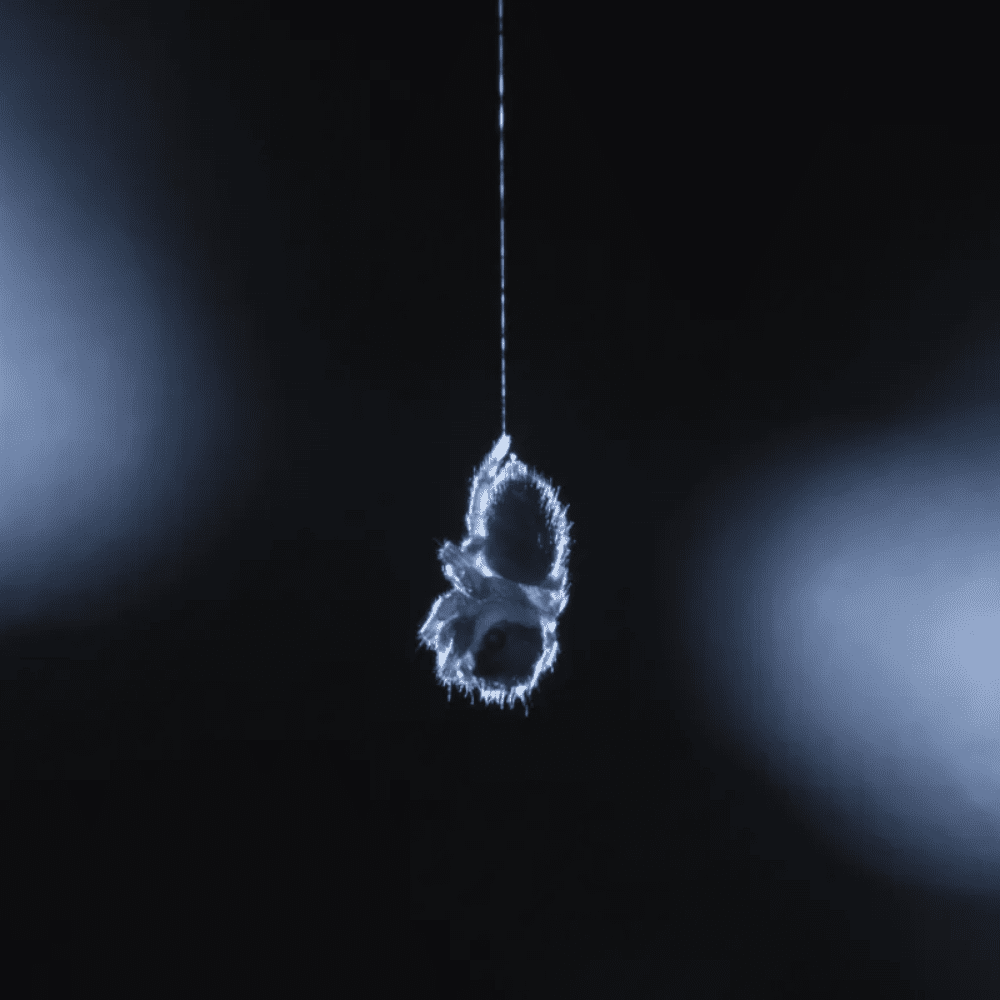

A Sleeping Spider

Dr. Daniela Rößler of the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior explained what a sleeping spider looks like. According to her, a spider usually begins the night by finding a safe place to perch. Next, they produce silk anchors from this spot in a zig-zag pattern, then drop them to the ground on a thin strand of silk. The entire time, they continue grooming themselves. Frequently, in pretty regular intervals, it seems like people can observe phases where there are erratic movements of the abdomen, spinnerets, or individual legs. These phases can be as mundane as one, two, or three legs noticeably twitching, or they can be extreme with all eight legs curled up, making it look like the spider’s dead.

The Eye Movement of Sleeping Spiders

Researchers studied nighttime footage of 34 juvenile jumping spiders, as they slept on camera, to watch for changes in their retinal tubes, which can move to adjust their gaze. Although jumping spiders can’t move their eye lenses, they do have retinal tubes that can move to adjust their eye focus. In addition, an animal’s sleeping patterns indicate where they are in the REM cycle. About the issue of whether spiders dream, there isn’t any conclusive evidence yet, but Rößler feels quietly confident that they do.