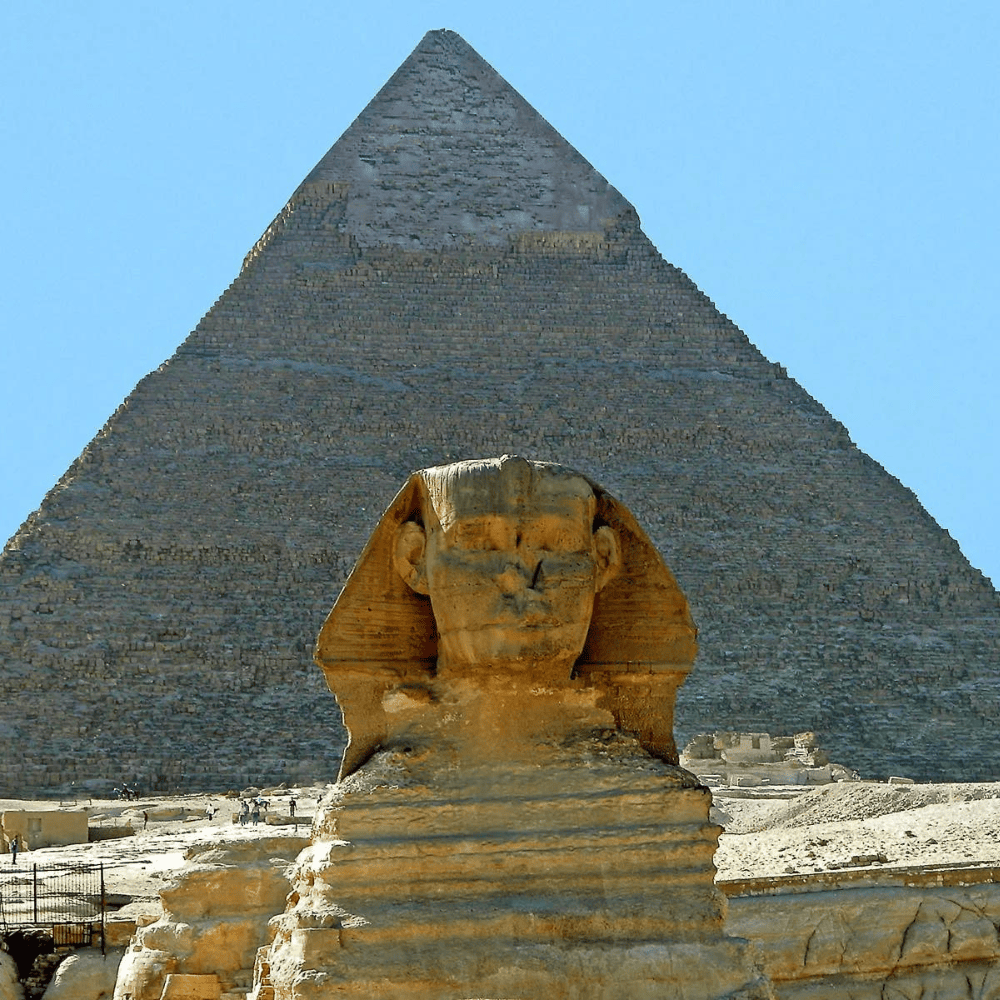

The pyramids at Giza have long been regarded as one of the enduring riddles of the Earth. These imposing constructions, of which the Great Pyramid alone contains over 2.3 million projecting sandstone and granite stones, have astounded researchers and antiquarians for many years, provoking inquisition into the practices utilized by the ancient Egyptians when shifting these monumental blocks. A team of historians and scientists embarked on a quest to unlock the secrets behind the pyramids’ construction. Their ingenious solution revolved around the idea that the ancient Egyptians harnessed the natural resources available to them – particularly, a tributary of the Nile.

A River’s Clues and a Papyrus Discovery

To validate their theory, researchers meticulously examined fossilized soil samples from the Giza floodplain. These samples were analyzed for traces of pollen and vegetation that would have been indicative of a waterway. The presence of these markers would confirm the existence of an ancient water route. The discovery of the Khufu Branch, a dried-up waterway that carried the colossal stone slabs to their destined location, provided the missing link. Interestingly, the inspiration for this discovery came from an unexpected source – a fragment of parchment found in the Red Sea. The fragment recounted the tale of Merer, an official tasked with transporting limestone via water to the Giza construction site. This historical account directly corroborated the research findings, shedding light on the ingenious use of water routes for moving the pyramid stones.

Uncovering the Past and Illuminating the Future

The journey to uncover this ancient feat involved painstaking efforts. Archaeologists dug as deep as 30 feet, unearthing millennia-old history from the bore samples. As a result of their meticulous work, 61 species of plants were identified. The study author emphasized that understanding the environment can illuminate the enigma of how the massive stones were hoisted into place, shedding new light on the monumental achievement of the ancient Egyptians.

Haines in Remote Alaska Houses the World’s First Hammer Museum

Dave Pahl’s fascination for tools took a new turn when he began his life as a homesteader in 1980, in the small town of Haines, Alaska. While there, he built an off-grid, one-room log house for his growing family and soon found himself being fully involved in using tools for most things. Eventually, he was drawn to his muse, the hammer!

The Hammer Museum

By 2002, Pahl’s vast collection of hammers, found in estate sales, eBay, and purchases on family vacations, led to the opening of the world’s first hammer museum. His cataloged collection of over 2,500 hammers, each with its own fascinating history, is now housed in a 100-year-old cottage he and his wife Carol bought in Haines to house his precious curios. To mark the museum’s location for cruise ship tourists and local visitors, he even erected a 19-foot tall hammer on the front lawn of the museum.

The Collection

The collection holds the world’s most ancient tool in its multiple forms, made from a variety of materials, like metal or wood, and designed for specific purposes or uses. In fact, as Pahl says, every profession had a hammer specific to its industry. Hence the museum has many varieties from a rock hammer used in the making of the Pyramid of Menkaure, Egypt, to 1960s small mallet drink hammers that New York’s bar-goers used to summon refills. Pahl admits that his personal collection of hammers expanded when visitors contributed to it, and when the family of a hammer collector, Jim Mau from Arizona, donated his collection to the museum after his passing.

The Importance of the Museum

The fascination of the Museum is not the great collection, but the character that Pahl is able to bring to each of the pieces. He is known as one of the most knowledgeable hammer collectors in the world today and has an answer for every inquiry — a child asking to identify a hammer for a school project or an art director seeking validation of the type of hammer to be used in a reenactment. To help collectors and the curious to know more about hammers, he self-published a book of 200-pages titled, The Improved Hammer: A Guide to the Identification, History, and Evolutions of the Hammer. He concludes that the purpose of building the museum was to preserve the anecdotes and the history of hammers and secondly, to give youngsters today a hands-on experience despite their preference for automation!